In the early 1820s, there was a great need for independent and dignified burial grounds for the District of Columbia’s growing free black community. Although slavery was legal in the Federal District, there was a growing community of free African Americans that was larger than the number of enslaved. In 1830, it represented more than 15 percent of the entire population of Washington City.

Enslaved people were buried at their enslaver’s expense, customarily in separate sections of their own family cemeteries or white cemeteries. An exception in Washington were two cemeteries established by churches in Georgetown for the burial of the enslaved and formerly enslaved associated with those churches. But free blacks had to bear all the costs of the burial of their family members.

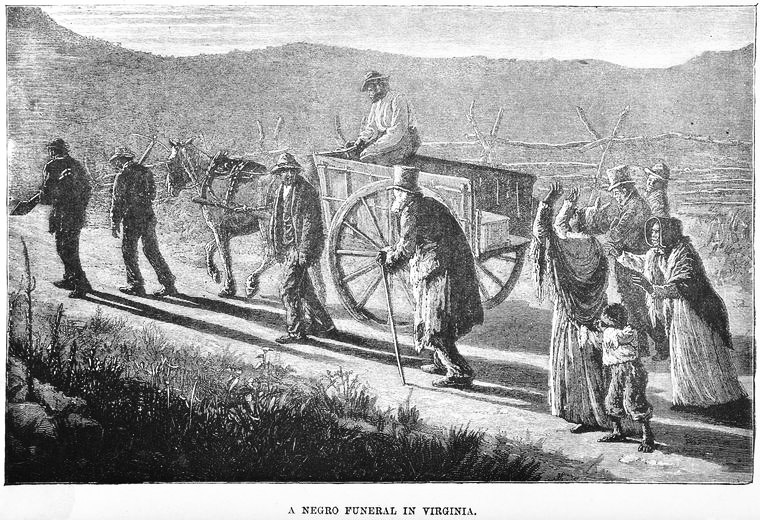

Funeral Procession, Virginia, Harper’s Weekly (Feb. 21, 1880)

In 1825, the Columbian Harmony Society was established by free African Americans as one of Washington, DC’s first mutual aid and burial societies for people of color. The benevolent society was formed to help defray the costs of illness and burials for its members, who paid an initiation fee and monthly dues.

The original members of the society were Francis Datcher (1790-1862, President), William Costin (1780?-1842, Vice President), John B. Hutton (Secretary), William Jackson (Treasurer), George Bell, and Joseph Warren. Other early members included Reverend John F. Cook, Benjamin McCoy, and William Slade.

Continue Reading

Find out more about the Harmoneon Cemetery by clicking on the articles below: